The Story Behind: It Is Well with My Soul

This is a new melody for the classic It Is Well with My Soul hymn lyrics. Read more about it and download free charts.

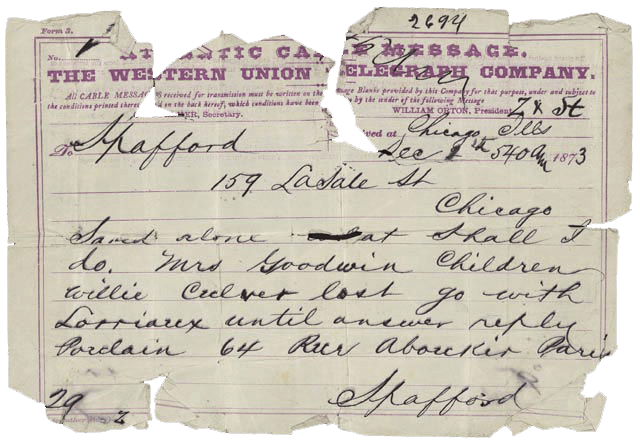

“Saved alone.”

The telegram arrived in Chicago on December 2, 1873, and with those first two words, Horatio Spafford’s world collapsed. But Anna’s message from Cardiff didn’t stop there. In the clipped economy of transatlantic cable, where every word cost precious money, she managed to convey the full horror: “Saved alone. What shall I do. Mrs Goodwin Children Willie Culver lost go with Lorriaux until answer reply Paris. Spafford.”

Even in her shock, Anna had presence of mind to list the dead: their friend Mrs. Daniel Goodwin, their neighbor’s boy Willie Culver, and sandwiched between these names, simply “Children.” No need to specify which children. All four. Annie, Maggie, Bessie, Tanetta. Gone.

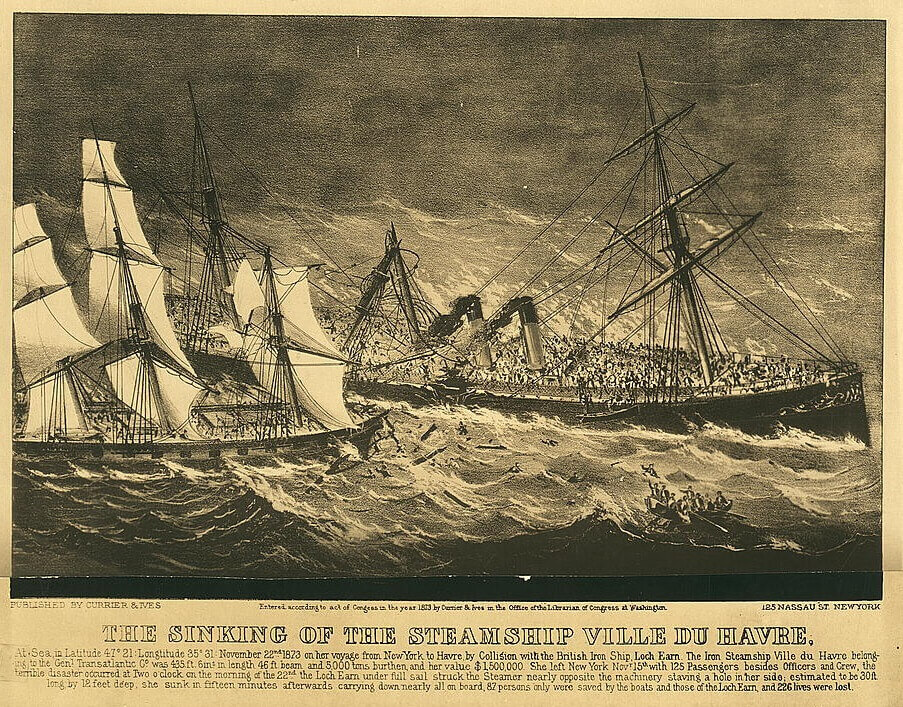

The SS Ville du Havre had collided with another vessel in the middle of the Atlantic and sank in just twelve minutes. Of the 313 souls aboard, only 87 survived. Among the 226 dead were four little girls who had kissed their father goodbye in New York just seven days earlier.

How does a father’s heart survive such devastation? How does faith endure when sorrows literally come like sea billows, rolling over and over until you can’t breathe?

For Horatio Spafford, the answer would come not in the immediacy of grief, but in the slow, mysterious work of grace. And when it came, it would pour out in words that have comforted millions: “It is well with my soul.”

The Man Behind the Words

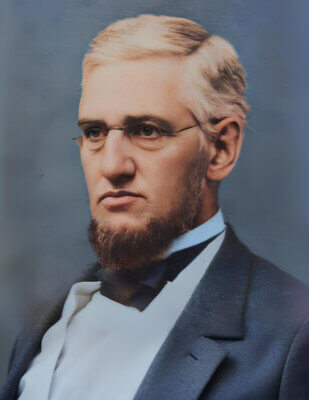

Horatio Gates Spafford wasn’t supposed to write one of history’s most beloved hymns. Born in North Troy, New York, in 1828, he was a successful Chicago lawyer, a Presbyterian elder, and a man of comfortable faith. He had the kind of life that produced contentment, not poetry – a thriving law practice, real estate investments, a beautiful family, and friendships with influential evangelicals like Dwight L. Moody.

But God rarely calls the comfortable to write songs of comfort.

Spafford’s first major trial came in October 1871 when the Great Chicago Fire reduced much of his real estate holdings to ash. In one night, years of careful investment vanished in flames that consumed over three square miles of the city.

Lesser trials might have produced bitterness. These trials produced something else – a deepening. Friends noticed Spafford leaning more heavily on Scripture, spending more time in prayer. When Moody announced his 1873 evangelistic campaign in England, Spafford decided to take his family along. They needed restoration, a change of scene, a chance to serve God in fresh ways.

But last-minute business detained Horatio in Chicago. On November 15, 1873, he kissed Anna and their four daughters goodbye at the dock, promising to follow on another ship. Anna later wrote that the girls were excited about the voyage, chattering about seeing England and meeting Mr. Moody’s singer, Mr. Sankey.

“You Are Spared for a Purpose”

Seven days later, in the early hours of November 22, the Ville du Havre was struck by the British iron clipper Loch Earn. The collision was devastating. The ship folded like paper and sank in minutes.

Anna Spafford remembered being thrown from her bunk when the collision occurred. She rushed to find her four daughters in the confusion. Amid the chaos as the ship began to founder, Anna clung to her youngest, Tanetta, but the force of the water tore the baby from her arms. Anna caught a glimpse of her two eldest daughters, Annie and Maggie, clinging to each other as the deck tilted steeply. She never saw Bessie again after the initial moments of the disaster.

Anna was later found unconscious, floating on a piece of debris, and was rescued by the crew of the Loch Earn. But years later her daughter Bertha, born after the tragedy, would find a scrap of paper on which Anna had written her recollection of those moments between death and life:

“I had no vision during the struggle in the water at the time of the shipwreck, only the conviction that any earnest soul, brought face to face with its maker, must have; I realized that my Christianity must be real. There was no room here for self-pity, or for the practice of that Christianity that always favors and condones itself and its own… Nothing but a robust Christianity could save me then and now…”

When Anna regained consciousness in the rescue boat, her first feeling was complete despair. How could she face life without her children? Her physical suffering was horrible, but her mental anguish was worse. Then, as she later told Bertha, something extraordinary happened.

“It was as if a voice spoke to her,” Bertha recounted. “‘You are spared for a purpose. You have work to do.’”

In that moment, Anna lifted her soul to God and dedicated her life to His service. One of her first coherent thoughts was a memory of “Aunty Sims” who had once pointed a finger at her and warned: “It’s easy to be grateful and good when you have so much, but take care that you are not a fair-weather friend to God!”

That phrase repeated in Anna’s mind as she floated between life and death. Her response would echo through the generations: “I won’t be a fair-weather friend to God. I will trust Him, and someday I’ll understand.”

The survivors were taken to Cardiff, Wales. From there, Anna sent her husband the telegram that would define the rest of their lives: “Saved alone…”

Birth of the Hymn: Separating Myth from Truth

Here’s where the story gets complicated, because the most dramatic version isn’t quite the whole truth.

The legend goes like this: Spafford immediately boarded a ship to meet Anna, and when the captain showed him the spot where the Ville du Havre went down, he returned to his cabin and penned “When peace like a river attendeth my way” right there on the spot, transforming his grief into gold in real time.

It’s a powerful image. And it’s partially true – but not in the way most people think.

Horatio did sail immediately to meet Anna. The captain did show him the approximate location where his daughters perished. And at that moment, gazing at the empty waves, Spafford reportedly said, “It is well; the will of God be done.” Those words – that resigned acceptance – were real. But the hymn itself? That would come later.

Ira D. Sankey, Moody’s music director and one of Spafford’s close friends, sets the record straight in his memoir. The actual writing of the hymn occurred in 1876, three years after the tragedy, while Sankey was staying with the Spaffords in Chicago. This isn’t secondhand speculation – Sankey was literally in the house when it happened.

Why does the myth persist? Perhaps because we want grief to make sense immediately. We want the redemptive moment to come in the midst of the storm, not years later in the quiet of an ordinary afternoon. But real healing rarely works on our timeline.

The writing happened when Sankey was visiting in 1876. Spafford showed him a poem he’d been working on, written on hotel stationery from Chicago’s Brevoort House. The manuscript shows evidence of careful revision – this wasn’t a spontaneous outpouring but crafted art born from seasoned grief.

The line “Thou hast taught me to know” was changed to “Thou hast taught me to say” – a subtle but profound difference. Knowing something in your head is one thing; being able to say it, to declare it, to sing it? That takes time. That takes testing. That takes grace working slowly through the deepest wounds.

The final line went through revision, too. Originally, Spafford wrote “A song in the night, oh my soul.” But he changed it to the much stronger “Even so, it is well with my soul” – turning the ending from a wish into a declaration, from hope into certainty. This kind of careful crafting doesn’t happen in the first flush of grief. It happens when pain has aged into wisdom.

What makes this story profound isn’t that a grieving father wrote a hymn. It’s that he took three years to do it – three years of living with loss, three years of learning to mean what he said at sea, three years of discovering that “it is well” isn’t a feeling but a choice, renewed daily, until it becomes true enough to sing.

What Spafford created wasn’t just a poem of personal grief – it was a carefully constructed theological argument for peace in the midst of suffering. Each verse builds on the last, moving from present trials through redemption to future hope.

The opening verse sets the paradox that defines the entire hymn:

When peace, like a river, attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou hast taught me to say,

It is well, it is well with my soul.

Notice the maritime imagery – not surprising from a man whose children died at sea. But Spafford doesn’t linger on the drowning. Instead, he uses water as a metaphor for both peace (the gentle river) and sorrow (the violent billows). Life brings both. The key is in line three: “Thou hast taught me to say.” This isn’t natural resilience or stoic philosophy. This is learned behavior, taught by God through suffering.

The second verse confronts spiritual warfare directly:

Though Satan should buffet, though trials should come,

Let this blest assurance control,

That Christ has regarded my helpless estate,

And hath shed His own blood for my soul.

Here Spafford borrows language from Paul’s thorn in the flesh (2 Corinthians 12:7) – Satan buffeting, trials coming. But the answer isn’t in our strength. It’s in Christ’s regarding our “helpless estate.” That word “regarded” is perfect – it means Christ has considered, looked upon, taken notice of our weakness. And His response? His own blood.

The third verse explodes in joy:

My sin, oh, the bliss of this glorious thought!

My sin, not in part but the whole,

Is nailed to the cross, and I bear it no more,

Praise the Lord, praise the Lord, O my soul!

The completeness of forgiveness – “not in part but the whole” – echoes Colossians 2:14 about our debt being nailed to the cross. But what makes this verse remarkable is the emotional punctuation: “oh, the bliss of this glorious thought!” Spafford interrupts his own sentence with wonder. Even in crafting, even in revision, he kept that spontaneous joy.

The hymn originally had six verses. Two are often omitted today, but they deepen the theology:

For me, be it Christ, be it Christ hence to live:

If Jordan above me shall roll,

No pang shall be mine, for in death as in life

Thou wilt whisper Thy peace to my soul.

This fourth verse echoes Philippians 1:21 – “For me to live is Christ” – and uses “Jordan” as the classic metaphor for death. But notice the certainty: “No pang shall be mine.” This from a man who knew the worst pangs imaginable.

The fifth verse (also often omitted) looks beyond death:

But, Lord, ’tis for Thee, for Thy coming we wait,

The sky, not the grave, is our goal;

Oh trump of the angel! Oh voice of the Lord!

Blessed hope, blessed rest of my soul!

“The sky, not the grave, is our goal” – this line has caused some theological debate, but in context, Spafford is clearly expressing hope in Christ’s return, not escapism. His daughters’ bodies were in the sea, but their destination was resurrection.

The final verse brings it all together:

And Lord, haste the day when my faith shall be sight,

The clouds be rolled back as a scroll;

The trump shall resound, and the Lord shall descend,

Even so, it is well with my soul.

The imagery comes straight from Revelation: clouds rolled back, trumpet sounding, the Lord descending. But it’s the final line that provides the hymn’s ultimate power. “Even so” – these two words from Revelation 22:20 mean “Yes, come, Lord Jesus.” But Spafford adds his refrain: even with the world ending, even with judgment coming, it is well with my soul.

The Hymn’s Journey Through Time

Philip P. Bliss, already famous for gospel songs like “Hallelujah, What a Savior,” set Spafford’s words to music. He named the tune “Ville du Havre” after the sunken ship – guaranteeing the tragedy would always be remembered alongside the triumph. Bliss himself would die in a train wreck that same year, 1876, at age 38.

The hymn first appeared in print in Gospel Hymns No. 2 (1876), the wildly popular collection used in Moody’s revivals. This gave it immediate exposure to thousands. Sankey sang it in meetings across America and Britain, often sharing the story behind it, which only increased its impact.

Early adoption was swift. By 1887, Southern Baptists included it in their hymnal. Methodists followed by 1905. Even denominations typically resistant to “gospel songs” eventually surrendered to its power. Today, it appears in over 500 different hymnals worldwide.

The text has remained remarkably stable, though editors made small changes. British hymnals sometimes included five verses instead of four. Some modern hymnals update “hath” to “has.” But the core message never changes.

Translations began almost immediately. French Protestants sang “Quel repos céleste, Jésus, d’être à Toi!” by the 1880s. Spanish-speaking churches embraced “Estoy bien con mi Dios,” often adding “Gloria a Dios!” to the refrain. In China, where Christians face persecution, “我靈得安寧” (My Soul Has Gained Peace) became a secret comfort. The Swahili version spread across East Africa. Korean Christians sang it through war and division.

Each culture made it their own. African choirs add rhythmic clapping. Latin American churches might include guitars and gentle sway. In India, accompanied by tabla and harmonium, it takes on an almost raga-like quality. The words remain; the expression adapts.

And today, Don Chapman’s new melody brings It Is Well with My Soul into the realm of modern worship. Ambient guitars, driving rhythms and a triumphant bridge (using the last verse lyrics And Lord haste the day…) transform Spafford’s 19th-century poem into something that feels both timeless and contemporary. Chapman’s version is an example of what every generation discovers anew: these words refuse to be confined to any single musical expression. Whether accompanied by pipe organ or worship band, the message transcends its medium. The sea billows still roll, but the soul still finds its peace. Sing this new version in your church – download a free chord chart, piano/vocal sheet music and vocal demo.

More Than Music: Cultural Impact

For nearly 150 years, It Is Well with My Soul has been sung in moments when the human heart needs steadying. Churches across traditions have made it a fixture at funerals and memorial services, not because of any marketing campaign, but because grieving people instinctively reach for it. Its refrain carries a quiet defiance — a way of saying that, though loss has come, faith still holds.

The hymn’s words have traveled far beyond the pews. They’ve been sung in hospital rooms where families kept vigil, at gravesides where the final earth was thrown, and in sanctuaries packed for community remembrance services. Missionaries have taught it across continents and cultures, translating it into dozens of languages while keeping its message unchanged.

It has reappeared during seasons of national sorrow — moments when congregations needed words that could bear the weight of collective grief. Whether sung in a country chapel or a city cathedral, accompanied by a full organ or nothing at all, its steady cadence invites people to join in until the truth sinks deep: even in the darkest night, it can still be well with the soul.

The Spafford Legacy: Beyond the Hymn

The sorrows like sea billows kept rolling. In 1880, four years after writing his hymn of faith, Horatio and Anna lost their young son, Horatio Jr., to scarlet fever. The boy was only four years old. For a family that had already buried four daughters, this fresh grief might have broken them entirely. Instead, it seemed to deepen their resolve.

In 1881, Horatio and Anna moved with their surviving children to Jerusalem, determined to live out a life of service. The community they founded, the American Colony, welcomed Jews, Muslims, and Christians alike, offering food, medical care, and education without any push to convert. In an age when missionary work almost always came with strings attached, this was radical compassion.

Over the years, critics accused the Colony of being a cult, painting Anna as a controlling leader after Horatio’s death. But much of that narrative can be traced back to the reports of U.S. consul Selah Merrill — a man later documented as holding deep personal and religious biases, including open antisemitism. By contrast, Ottoman records and contemporary accounts show a community respected and trusted in Jerusalem. During World War I, the Colony ran soup kitchens feeding thousands daily, managed military hospitals, and even documented major historical events for both the Ottoman authorities and world leaders.

It’s true that Horatio’s theology shifted in his later years, embracing ideas outside evangelical orthodoxy. But when he wrote “It Is Well with My Soul” in 1876, his beliefs were firmly rooted in the Gospel truths the hymn proclaims. The song stands on its own doctrinal integrity, unclouded by what came after.

Anna, far from the one-dimensional figure in some retellings, carried forward the Colony’s humanitarian mission for decades, joined by their daughter Bertha Spafford Vester. Bertha, who lived in Jerusalem until her death in 1968, remembered her mother’s faith as a lived reality born out of tragedy — a vow never to be a fair-weather friend to God.

Today, the American Colony Hotel still stands in Jerusalem. Displayed are photos of four little girls in Victorian dress — Annie, Maggie, Bessie, and Tanetta. They are forever young, forever mourned, and forever the reason a grieving father once wrote words that continue to heal: It is well with my soul.

Timeline of Tragedies and Triumphs

- October 8–10, 1871 – Great Chicago Fire destroys much of Spafford’s real estate investments

- November 15, 1873 – Anna and four daughters sail for Europe on the SS Ville du Havre

- November 22, 1873 – Ville du Havre sinks in the middle of the Atlantic; all four Spafford daughters perish

- December 2, 1873 – Horatio receives Anna’s telegram containing the words “Saved alone”

- December 1873 – Horatio sails to meet Anna in Wales

- 1874–1875 – Spaffords return to Chicago and begin rebuilding their lives

- 1876 – Horatio writes “It Is Well with My Soul” in Chicago during Ira Sankey’s visit

- 1876 – Philip P. Bliss composes the tune “Ville du Havre”

- 1876 – Hymn published in Gospel Hymns No. 2

- December 1876 – Philip P. Bliss dies in a train accident

- 1880 – Spafford’s four-year-old son, Horatio Spafford Jr., dies of scarlet fever

- 1881 – Spafford family moves to Jerusalem and establishes the American Colony

- September 25, 1888 – Horatio Spafford dies in Jerusalem

It Is Well with My Soul by the Numbers

- 12 — Minutes it took for the Ville du Havre to sink

- 226 — Total lives lost in the shipwreck

- 87 — Survivors from 313 passengers and crew

- 500+ — Hymnals that have included “It Is Well with My Soul”

- 50+ — Languages into which the hymn has been translated

- 100M+ — Estimated YouTube views of various performances

- #1 — Ranking among most-requested funeral hymns

- 150 — Years the hymn has been continuously sung (1876–2026)

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q: Does the Bible actually say “it is well with my soul”?

A: No, the exact phrase “it is well with my soul” is not in the Bible. It comes from Horatio Spafford’s 1876 hymn, inspired by his faith after losing his children at sea. The words echo biblical themes of peace in trials, especially verses like Isaiah 66:12, Psalm 46:1–3, and Philippians 4:7 about God’s comfort and steadfastness in hardship.

Q: Is It Is Well with My Soul a funeral song?

A: Yes, it is one of the most popular Christian hymns used at funerals and memorial services. Its message of trusting God through grief has made it a choice for generations of mourners. While it was written from personal tragedy, its lyrics focus on hope, redemption, and eternal peace, making it fitting for honoring a life of faith.

“It Is Well (Peace Like a River)” Lyrics Video

Download a FREE chord chart, piano/vocal sheet music and MP3 vocal demo for It Is Well (Peace Like a River). The link to the free download is in the Hymncharts newsletter. If you already receive the newsletter, scroll down to find the link. If you’d like to receive the newsletter, enter your email address below and you’ll instantly receive the newsletter with the link (check your spam folder if you don’t see it!)